Learn More About Benchmarking and Transparency

What is Energy Use Benchmarking?

Energy use benchmarking is measuring a buildings energy use over time, and comparing it to other similar buildings.

The DOE defines energy benchmarking as “The process of accounting for and comparing a metered building’s current energy performance with its energy baseline, or comparing a metered building’s energy performance with the energy performance of similar types of buildings (based on use, such as comparing the energy performance of a hospital to that of other hospitals). Benchmarking can be used to compare performance over time, within and between peer groups, or to document top savings from conservation measures.

References and Additional Resources

What are the Benefits of Benchmarking?

Energy benchmarking helps us understand our energy use, so that we can make changes that will help plan and prioritize limited resources in order to save money and save energy.

Energy benchmarking helps us understand our energy use, so that we can make changes that will help plan and prioritize limited resources in order to save money and save energy.

According to ENERGY STAR® “Energy expenditures average more than $2 per square foot in commercial and government buildings, making energy a cost worth managing. By making energy performance measurable and visible, building owners can improve the efficiency of their buildings, which can drive new investment and create an estimated 5 to 15 green jobs per $1 million invested. Efficient buildings are also more profitable and more valuable at resale, which can increase property tax revenues. Building owners seek benchmarking data to differentiate a building or company, help value rental rates, and inform the sale or acquisition of existing buildings.”

What is Disclosure or Transparency?

Building benchmarking policies often include a component “disclosure” or “transparency”. These policies typically require either regular reporting to the government or making energy performance data available when a property is sold or leased. Most government reporting programs include a provision for that information to be made public in some manner. When performance data is disclosed, there is greater knowledge in the market that will help tenants, building owners/operators, as well as those purchasing buildings consider cost of operating a building. This information also can indicate the quality of the building and how well it is being operated. However, there can be significant concern in the building owner/operator segment that building data may be disclosed in a way that does not allow for accurate comparisons. To remedy this, it is particularly important to make sure that the building being compared are similar.

Another option that has not been pursued by Cities, but may be useful, is to follow a model similar to DOE’s building performance database. Different from the Philadelphia and Washington DC model, all data is aggregated with no specific building identification information provided. A building owner interested in how they compare with their peer group can choose a variety of building, climate, use characteristics that will allow them to do an apples to apples comparison between their facility and others in the city. This is similar to the Chicago model, however, it allows for a bit more of a dynamic comparison. This model is important to consider if the City is facing significant challenges when developing its transparency policy.

References and Additional Resources

What are the types of benchmarking programs?

There are three main types of benchmarking programs: government building programs, voluntary benchmarking programs, and mandatory benchmarking programs. Communities often begin with benchmarking their own government facilities.

Government Buildings

Many communities want to lead by example and want to understand how benchmarking works for themselves before designing a program for other buildings in their community. Therefore, these communities begin the process by benchmarking their own energy use.

Benefits:

Government building benchmarking lets communities lead by example, demonstrating that energy benchmarking:

- provides objective data on energy use and the benefits of improvements;

- increases awareness, which may lead to behavior change;

- facilitates planning;

- identifies best practices that can be used by others

- provides a baseline for measuring improvements, and helps to develop a comprehensive energy management action plan

- provides data to evaluate the business case for capital investments in energy retrofits.

Show Examples

References and Additional Resources

Voluntary

Voluntary programs are designed to encourage building owners to benchmark their energy use. Communities may use their successes and lessons they learned in their own benchmarking programs to design and communicate the benefits of a voluntary program.

Benefits:

Voluntary programs encourage other building owners/operators in the community to benchmark their facilities. However, there is no requirement to benchmark as there are with mandatory programs. These programs typically communicate the successes of the participants in the programs to encourage additional buildings to participate.

Show Examples

References and Additional Resources

Mandatory

Mandatory programs are those where a community has adopted a policy requiring energy benchmarking.

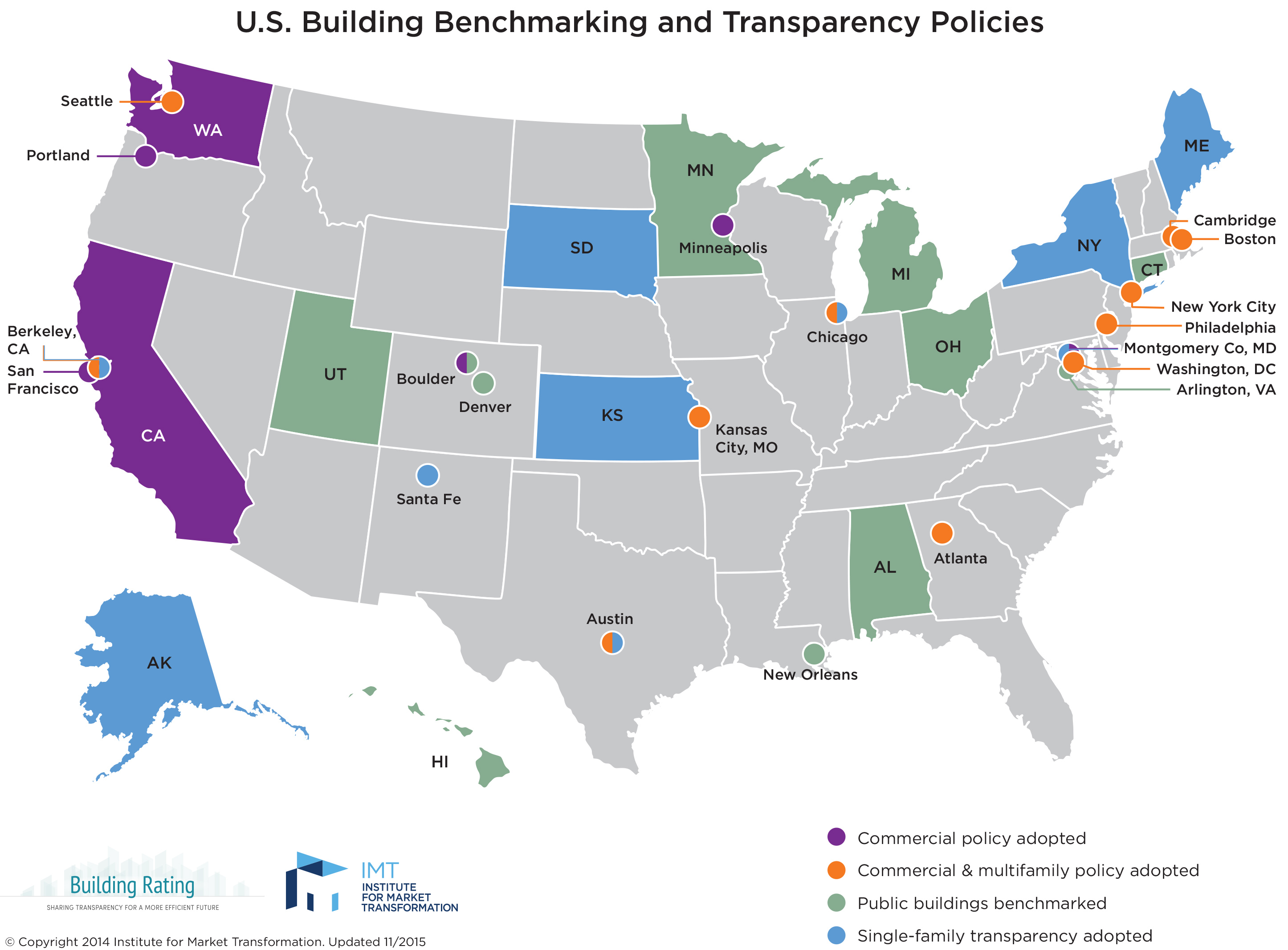

U.S. Building Benchmarking and Transparency Policies

Benefits

A mandatory program assures the participation of most of the covered properties, it provides additional information for comparison, and increased participation in benchmarking should lead to greater energy savings.